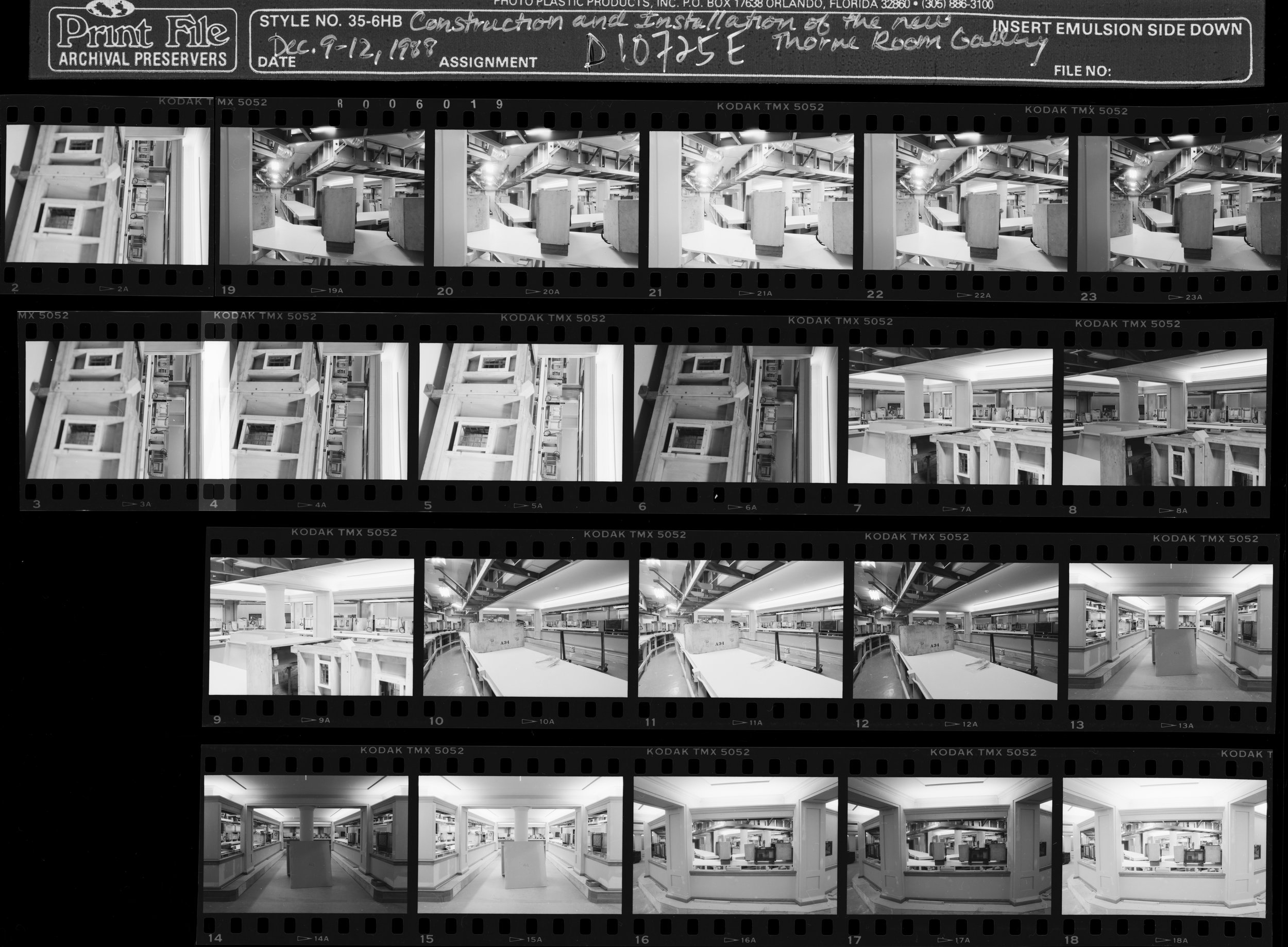

They implemented appropriate environmental controls including an independent HVAC system for fine-tuned temperature and humidity control. They also installed programmable LED lighting and a variety of security tools - video, alarms, and locks. Additionally, they oddy tested materials that were used to build the cases, which ensured the exhibition furniture is doing no unintended harm to materials on display. These cases are movable, which allows for more nimble and independent control of the exhibits by library staff - they no longer need crew to help them move cases. The cases feature spaces beneath for silica to allow for even greater control of humidity. The library has several designs of these cases available for use, and they also gained storage space dedicated for storing cases. Other features in the newly redesigned exhibition space include a ceiling mounted projector, floor outlets and AV ports, and a poster rail.

The exhibition space rotates through an average of four exhibits per year, which correlates with the university’s quarter system. The library has one staff dedicated to this work, and the curators rotate - they may include archivists or special library staff, general librarians, faculty, students, or outside curators and donors. There has been a surge of interest in the last few years for university class students to curate exhibits. This can be challenging in a class of 30 students, as cases get crowded. It also means that the exhibition schedule may be filled multiple years in advance, limiting how faculty can design their curriculum. Library staff are evaluating how to strike a balance, and are investigating whether web exhibits may work best for these situations.

Generally, projects begin roughly 12 - 18 months from the anticipated date of installation. The library is in the process of developing a more formal proposal process. The presenter provided a sample of the timeline for exhibits, which includes development - conceptualization, item selection, and exhibit design - and production - digitization, text production, graphic design, web exhibit production, production of collateral materials.

For the exhibitions’ budgets, most costs are generally covered by the university. The ability to use existing cases and vitrines helps to this end, as do dedicated staff at the library. Printing graphics is usually covered under the general operating budget, and occasionally there may be fees to pay for loans. In cases where curators want to design a full-fledged publication that corresponds to the exhibit, they must find their own source of funding.

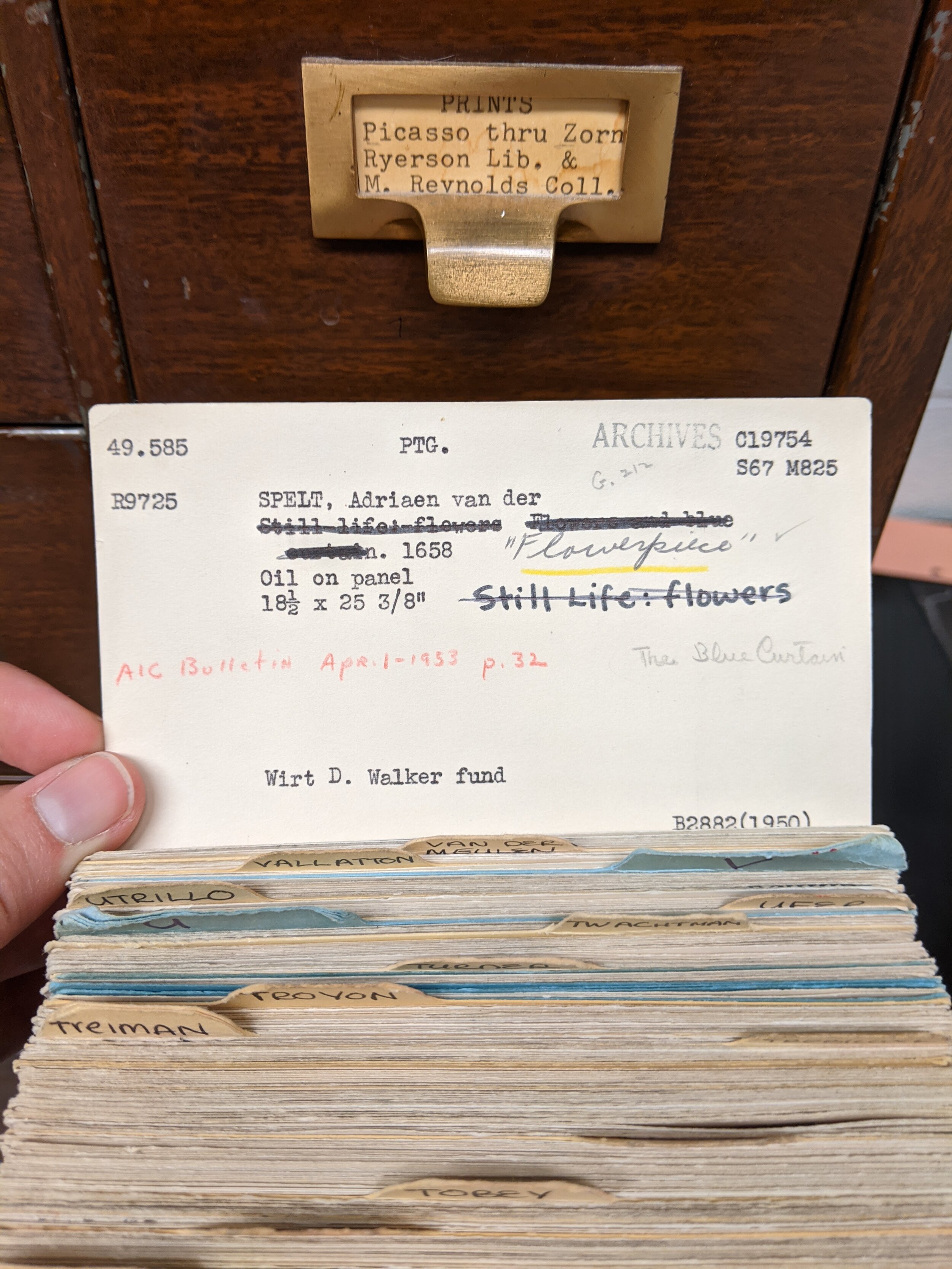

As it relates to the selection of items to be exhibited, library staff have found that curators can most easily find materials in the general collection at the university. Generally, it requires more guidance from special library and archives staff for the selection of rare materials - this may include teaching curators how to use finding aids, for example. Wherever possible, they try to source materials from the university system for exhibition. When loans need to be procured, staff try to use the opportunity to inform new acquisitions moving forward.

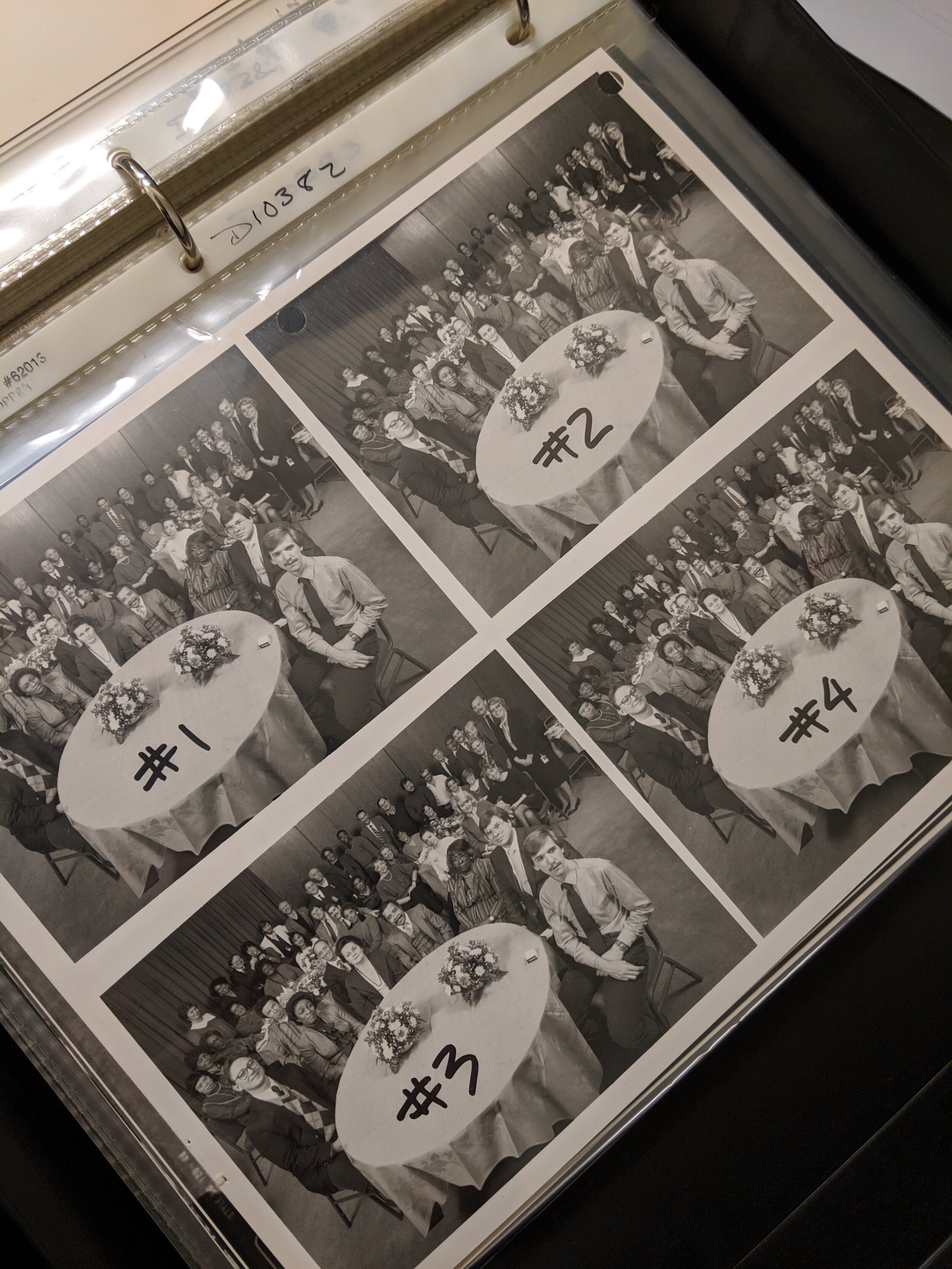

The digital library team works with the exhibition staff member to develop web exhibits that correlate with the physical exhibits. The design for these experiences is similar in look and feel to Omeka sites, a platform with which faculty and staff are often already familiar. In conjunction with these interactive experiences, the digital team also creates downloadable PDF files with full text. In this way, these exhibits can live on after they have been de-installed, and there is documentation of the work and research. Copyright is one important factor to consider in web exhibits, and generally, they try to err on the side of caution in not digitizing and publishing online materials that are in copyright (held by external agents). Occasionally, the team works with ARS to secure licenses to selectively publish important materials. This also informs how they photographically document the physical exhibits - generally, they document cases as a whole rather than individual objects.

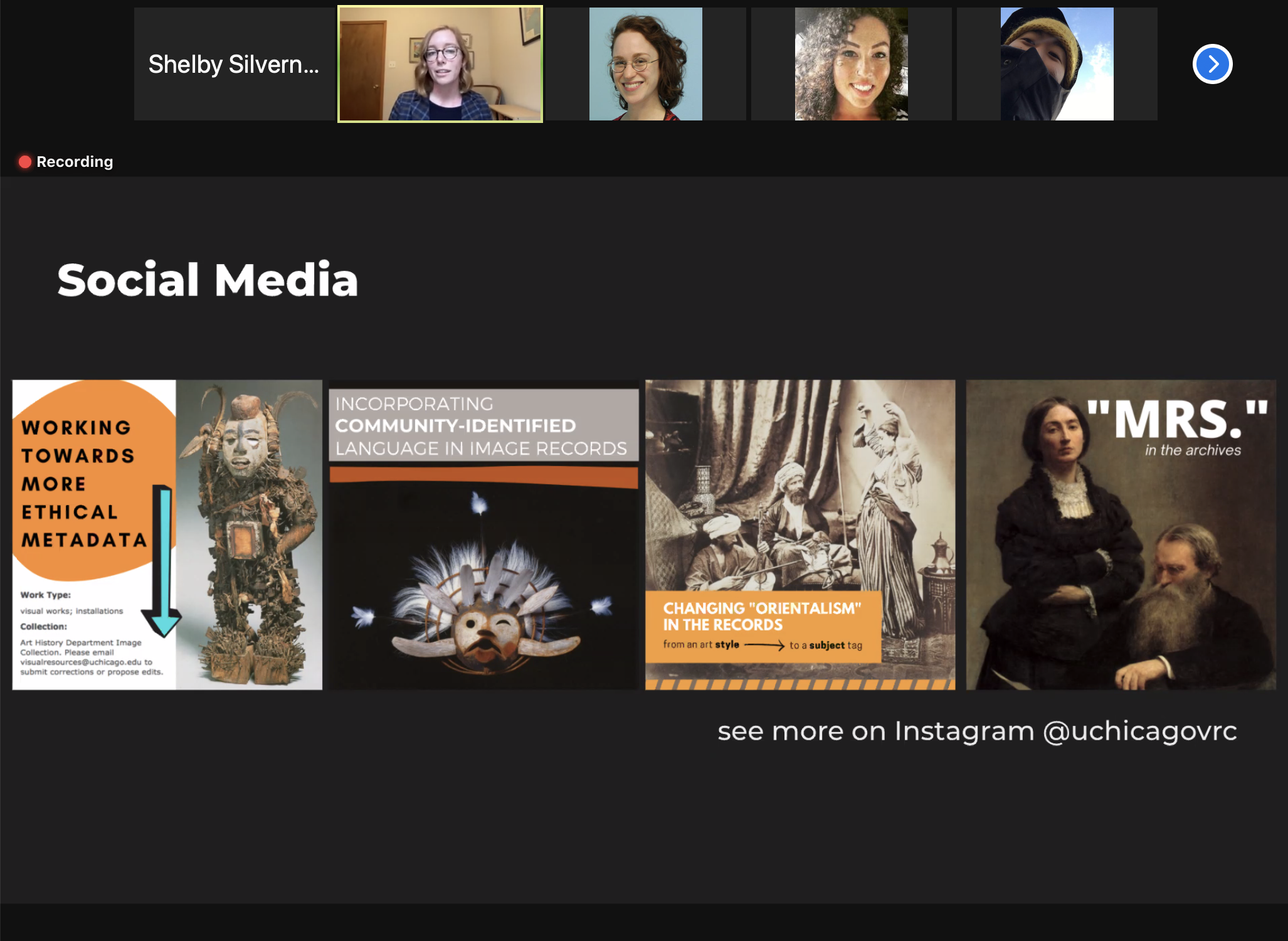

The library leverages existing staff and tools for PR and outreach. Library communications helps to get the word out on campus about exhibitions. Staff try to align programs and events with both the exhibit and any other initiatives on campus. Events may include tours, conferences, classes, lectures, author or artist talks, and general receptions.

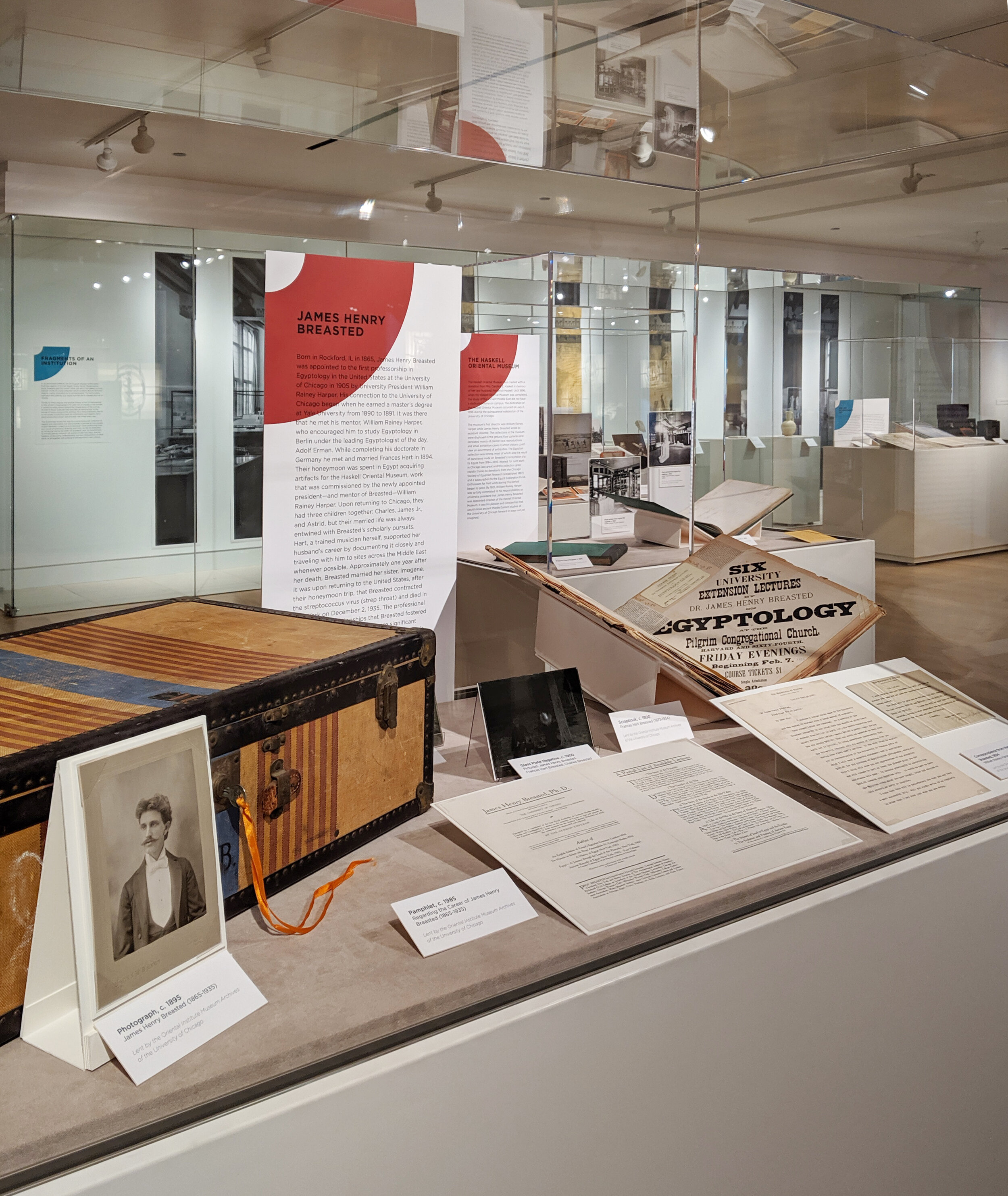

The presentation next shifted to a discussion by a staff member at the Oriental Institute (OI), a museum on-campus at the University of Chicago:

“The Oriental Institute was founded in 1919 by James Henry Breasted with the financial support of John D. Rockefeller Jr., and was originally envisaged as a research laboratory for the investigation of the early human career that would trace humankind’s progress from the most ancient days of the Middle East. The goal of the Oriental Institute is to be the world’s leading center for the study of ancient Near Eastern civilizations by combining innovation in theory, methodology, and significant empirical discovery with the highest standards of rigorous scholarship. The Oriental Institute Museum was opened to the public in 1931. (The Oriental Institute, n.d.)

She provided us with some background information about the museum, including its archival collection scope of faculty records, still and moving images, institutional records, and archaeology dig records. Much of this collection has been hidden over the years, as is common with many archival collections given backlogs, but staff recognized that processing to facilitate access is important, especially with their 100 year anniversary. Outreach via this exhibit was another helpful way of raising awareness and visibility of the museum and its holdings.

She made the case that archives are examples of and critical to cultural heritage as much as museum collections objects are. In the context of OI, such archival materials include documentation of now-destroyed ancient sites, and records that tell the story of provenance for historic objects. To make the archives more visible and relevant, they have pursued several projects. One of these includes the Cultural Heritage Experiment, where OI lends reproductions of archival materials to students at the University of Chicago. Students may pick from a selection of digitized images and records, and then have the opportunity to bring the archives into their own personal spaces. OI staff gather stories from students about their experiences, and from this, they are building an archive of the Cultural Heritage Experiment.